Study shows how SARS-CoV-2 infects cells in mouth, possibly leading to oral symptoms

A study examining the role of the oral cavity in SARS-CoV-2 infection has found evidence the virus infects cells in the mouth, which could explain why some patients with COVID-19 experience taste loss, dry mouth and blistering. The research also found that saliva is infectious, indicating the mouth may play a part in transmitting the virus deeper into the body or to others.

"After months of collaboration, our study shows that the mouth is a route of infection as well as an incubator for the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19," said Kevin M. Byrd, D.D.S., Ph.D., one of the lead researchers and the ADA Science and Research Institute’s Anthony R. Volpe Research Scholar. "This foundational work will help direct our next studies to further understand at the molecular level why individuals are presenting with altered/loss of taste and dry mouth after infection during COVID-19, why some individuals are demonstrating these effects six-plus months after the first infection, and if/how we can come up with treatment strategies to help these individuals recover."

The research from the National Institutes of Health and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was published March 25 in Nature Medicine. Dr. Byrd, then an assistant professor in the UNC Adams School of Dentistry, led the study with Blake M. Warner, D.D.S., Ph.D., assistant clinical investigator and chief of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research's Salivary Disorders Unit.

Prior to this study, not much was known about how the oral cavity is involved in SARS-CoV-2 infection. The upper airways and lungs are known to be primary sites of infection and saliva can contain high levels of the virus, but scientists do not entirely know where the virus in saliva comes from, according to an NIH news release. In people with COVID-19 who have respiratory symptoms, the virus could potentially come from nasal drainage or phlegm coughed up from the lungs, but that may not explain how the virus gets into the saliva of people who do not experience those symptoms.

"Based on data from our laboratories, we suspected at least some of the virus in saliva could be coming from infected tissues in the mouth itself," Dr. Warner said.

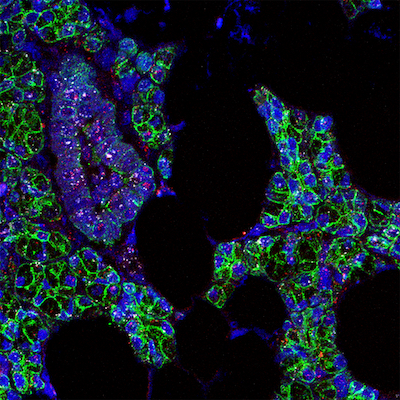

The researchers tested this theory by surveying oral tissues from healthy people to identify areas of the mouth that are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. They found some cells in the salivary glands and tissues lining the oral cavity contained RNA for two key "entry proteins" — the ACE2 receptor and the TMPRSS2 enzyme — that allow the virus to enter cells, thus making them susceptible to infection. A small number of the salivary gland and gingival cells contained RNA for both the ACE2 receptor and the TMPRSS2 enzyme, increasing the cells' vulnerability because the virus is believed to need both entry proteins to gain access to cells.

The research team looked at oral tissue samples from people with COVID-19 for evidence of infection, finding SARS-CoV-2 RNA was present in slightly more than half of the salivary glands collected from patients who had died. In salivary gland tissue from one of the people who had died and from a living person with severe COVID-19, they also found specific sequences of viral RNA that indicated cells were actively making new copies of the virus.

In people with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19, cells that shed from the mouth into saliva were found to contain RNA for SARS-CoV-2 and the entry proteins, indicating infected oral tissues appear to be a source of the virus in saliva. The scientists exposed saliva from eight people with asymptomatic COVID-19 to healthy cells grown in a dish, and saliva from two of the volunteers caused the healthy cells to become infected, showing it is possible for asymptomatic people to transmit the virus to others through saliva.

"Asymptomatic spread is the Achilles’ heel of this pandemic, and we found the virus can be present in the saliva of asymptomatic individuals and also in the saliva of those who experienced changes to their taste/smell," Dr. Byrd said. "If changes to your taste/smell are your only symptom, it is still important for you to get a COVID-19 test and self-isolate for the good of your community."

The researchers collected saliva from a separate group of 35 NIH volunteers with mild or asymptomatic COVID-19 and found those who experienced symptoms were more likely to report a loss of taste and smell if they had virus in their saliva, suggesting oral infection could be the reason for oral symptoms.

The research also indicates the mouth could play a role in transmitting SARS-CoV-2 to the lungs or digestive system through saliva that contains the virus from infected oral cells.

"When infected saliva is swallowed or tiny particles of it are inhaled, we think it can potentially transmit SARS-CoV-2 further into our throats, our lungs or even our guts," Dr. Byrd said.

The study's findings will need to be confirmed in a larger group of people, and more research is needed to determine the exact nature of the mouth's involvement in SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission inside and outside the body, according to the NIH news release.

"By revealing a potentially underappreciated role for the oral cavity in SARS-CoV-2 infection, our study could open up new investigative avenues leading to a better understanding of the course of infection and disease," Dr. Warner said. "Such information could also inform interventions to combat the virus and alleviate oral symptoms of COVID-19."